(A short fiction I did this June, exploring anti-heroes and orange stones. 2,100 words, approximately a 9-minute-read.)

Froilan Dayap’s eyes rolled backwards. His grip loosened. His calf muscle melted. He laid there, naked and tangled in bedsheets that looked like the underside of mammatus clouds. The slit in the curtains allowed the morning sun to hit one of his eyes, painting lovely shades of fleshy hues in his mind’s eye. Beads of sweat started to form on his brows. He kept still. He was too sluggish to move his head. This morning workout was just what he needed before a hectic day at the office.

As the warm waves started to subside, a shrill tone from the bedside table snapped him out of the carnal euphoria. His phone was ringing, and Eddie’s name was on the screen.

“Later boss.” He switched the phone to silent mode.

Lying supine, Froilan grabbed the tissue box by the bedside and began to wipe the pool of bodily liquid that gathered in his belly button. Thank god for this natural catch basin, he thought. The clean up process was conducted with utmost care as he did not want to spill anything on the brand new duvet or the brand new carpet. He was protective of his domain, even from himself. This concrete box, and the tchotchkes that live in it, were all that he had to show for the eight years he had worked at the Office of the Building Official.

His unit was small. At eighteen square meters, it was right at the limit allowed by law for a medium-cost condominium. He still bought it of course, because one, it was near his workplace; two, he was part of the city board that approved the residential development. Froilan made sure to mention that fact to the head of sales when he took the thing on loan. A small perk for a thankless job.

The space was spartan except for a collection of toy figures with oversized heads, still in their respective boxes. These boxes were then piled nine high and ran the length of the longest wall. On the bedside table, beside the tissue box, was a framed photo of him and his parents. He was six when liver cancer took his father. The day after the burial, his mother drove him to his father’s relatives in Makati to run an errand. She never returned to pick him up. He kept their family photo as a reminder that he had parents once, and for a few years in his childhood, he was like most kids—without worry, without annoying cousins, without strict aunts, without care of playing by the rules, without the pressure of always being right.

As the cold shower washed off the pleasures that still clung to his body, his phone vibrated on the toilet counter. He weighed his options: pick up the phone, or to let the water drown the buzz of the electronic glass slab. He let it vibrate for three more cycles and then finally when he couldn’t take any more, he swiped to the right with wet hands.

“Who’s this?” Froilan asked. Bringing the phone to the toilet was a bad idea.

“Who else?” the voice asked back. “You are not answering my calls.”

“My phone’s on silent mode. I did not…”

“It’s 9:30!” the voice cut him off.

“I’m on my way Eddie.” Froilan turned the shower spigot off, quick and quiet like. “I am walking to the office as we speak.”

“You better be. I just saw yesterday’s construction photos. It’s not funny.”

Before he could reply, the line went dead.

Froilan was on the move. Within seven minutes, he got dressed and closed the front door behind him. The city hall was a fifteen-minute walk from where he lived. On an ordinary day, the journey to work would take him through a gauntlet of narrow sidewalks, crooked alleys and a string of cheap motels (where he thought he saw a couple of his officemates walk out from one of its side doors). But it was the first Tuesday of the month and he was late. Froilan hailed a tricycle and asked for the one-hundred-peso special trip.

The open-air transport scooted with a speed not worth the bill, but it cut through his usual route in half the time, so he was still thankful. The rushing wind dried the sweat on his shirt and cooled his chest. He found the time to finally gather himself. Every first Tuesday of the month, his department conducted a management committee meeting, ‘mancom’ as the non-contractuals called it. This meeting was where city projects were created and taxpayer money got spent if there were any that trickled down their way. This was where a rank-and-file can share his bright ideas and get promoted or be left humiliated in the nondescript position he was holding for the last eight years.

Froilan arrived at the Office of the Building Official at exactly a quarter to ten. The place smelled of urine and fresh bond paper. The cheapest way, and by result, the most conventional way of producing blueprints involved dousing the papers in chemicals containing ammonia. Ammonia smelled like cat piss and released vapors that hurt the eye. Froilan cannot tolerate the scent despite years of handling the permit applications. This was why he stamped urine-smelling documents with ‘re-submit as digital print’ every time he encountered them. Yes, it will add weeks to the building permit process, poor applicant, but Froilan worked best when his nose was not inconvenienced. On one occasion, a colleague inquired about his anal attitude towards the applications, to which he replied, “I’m doing everyone a favor.”

He made a quick reconnaissance of the office. The meeting room on the south corner was unlit. There was no movement, no clicking of keyboards. Opposite that, Engr. Taborete’s office was vacant and still. Very good omens. His boss was late and this meant that the mancom meeting, as the case sometimes, was rescheduled to three in the afternoon. This meant that he still had time.

He hurried to his seat and made an effort to look busy. He was booting up his workstation when a tall shadow approached his periphery. Without looking he knew who it was.

“Finally,” the shadow said.

Froilan wanted to roll into a ball. “I woke up with a headache and LBM… was about to file a sick leave then I remembered it was Tuesday.”

“Oh? Should I be thankful?” A brief pause. The tall shadow continued, “I have been calling the whole night. Are you ignoring me?”

“Eddie, you know I don’t answer calls after five. What’s so urgent?” Froilan asked with half-feigned curiosity.

Even though senior by rank, Eddie Torqueza was a million years away from being a respected professional. It helped that he came from a prestigious school, and that his 6’2” frame won them the inter-department sports fest last summer, but Froilan knew that Eddie was not as smart as most people thought he was. He was an average guy who happened to speak well. He just had a way with words.

“Why the fuck is the new cemetery bright orange?!” Eddie was half-shouting before he caught himself. He took a deep breath and held the air in his chest before continuing behind clenched teeth, “Froilan, what-the-fuck happened while I was on leave?”

“I can explain. Please, sit down.” Froilan motioned him to the chair beside his desk. Seeing that Eddie will not budge, he continued, “The supplier ran out of marble slabs. I had to find a stone with equivalent specs.”

Eddie’s eyes were pearlescent balls bulging out of an elongated skull. The skin on his face was crimson with hits of burgundy and lavender.

“Same specs?”, he asked. “Last time I checked, cemeteries were supposed to be white. The approved design was white. The approved material was white. Why does my cemetery project look like a fruit?!”

Froilan took account of all the possible answers before opening his mouth. As the temporary Officer in-Charge of the Makati City Columbarium Project, he had hundreds of transactions everyday. It could not have been humanly possible to keep track of everything. That’s one. Two, he had interns on his team. God knows what they approved. Three, orange was not that bad of a color.

“The supplier had me approve an alternative finish for the vaults. What was presented to me was totally different from what was installed and will be punchlisted accordingly,” he said, putting in as much construction jargon as he can.

On cue, Eddie vanished and then reappeared carrying a square orange object in his large gorilla hands. It’s about four inches by four inches wide by one inch thick, with chamfered edges. He laid it with intentional thud on Froilan’s table.

“Do you know what this is?” A rhetoric. “This is the sample swatch of the stone installed in the cemetery right now. And look here.” Eddie pointed at a scribble on one of the corners of the sample. “That’s your signature Froilan, with last week’s date on it. You approved this sample and you can’t lie yourself out of this, bud. Not this time.”

Froilan looked Eddie in the eye and felt an unexpected calm. There was a soothing familiarity in them. Those were the same eyes that his mother wore when she left him years ago. Those were the eyes of his cousins that framed him for the money they took from their mother’s purse to buy a bootleg copy of a playstation game. Those were the eyes of the aunt that believed the lie. His parents abandoned him, he must have deserved it, they surely thought.

Staring at the orange marble in front of him, Froilan experienced clarity he never had for a long time. He will not be made to admit another mistake ever again. Never mind the fact that he partied, got drunk, and flirted with a well-endowed silver-tongued sales rep. Or that he got duped into purchasing something that nobody else wanted, an orange stone. Or that he signed the damned sample in a dark VIP room, a sample that will be used, not just one, but for 10,000 columbarium vaults. Never mind those things. The man in front of him only has to know one fact.

“Eddie,” he said. “I saw you and Thea walk out of Sogo last week.”

The tall figure stood frozen, speechless.

“Your wife doesn’t know. The office doesn’t know. But I know.” Froilan pointed at his chest with his crooked middle finger. Then with the same finger, he pushed the marble sample back to Eddie, “Let’s keep it that way.”

Froilan eyed the creature in front of him. It stood motionless for a time, boiling and pensive. With abrupt motion, the creature took the marble sample and huddled back to its lair right beside the office pantry. As Eddie’s figure disappeared through layers of office cubicles, Froilan thought that 6’2” was actually not that tall.

***

The Krispy Kreme that Engr. Taborete brought was soft and sweet, the perfect combination to the brewed coffee that Froilan served the group. When it was Eddie’s turn to update, he proudly shared the new trend of celebrating life in graveyards and the upcoming color of the year, Tangerine. Engr. Taborete was skeptical, initially, but caved in at the end. He said that it was okay as long as the Mayor was informed of the change before the new stones were purchased. Eddie assured him that the protocols were followed. His co-worker really had a way with words, Froilan thought.

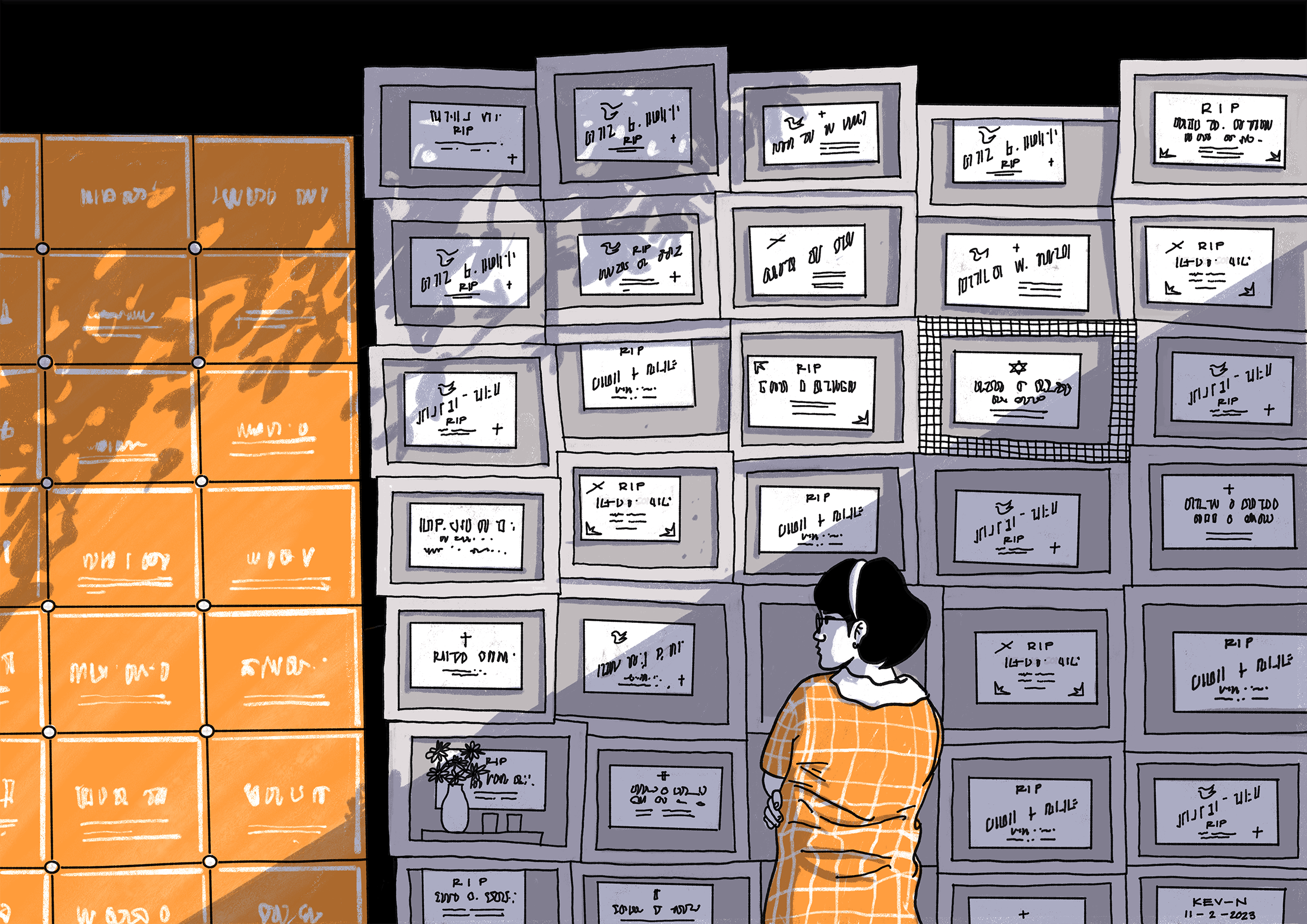

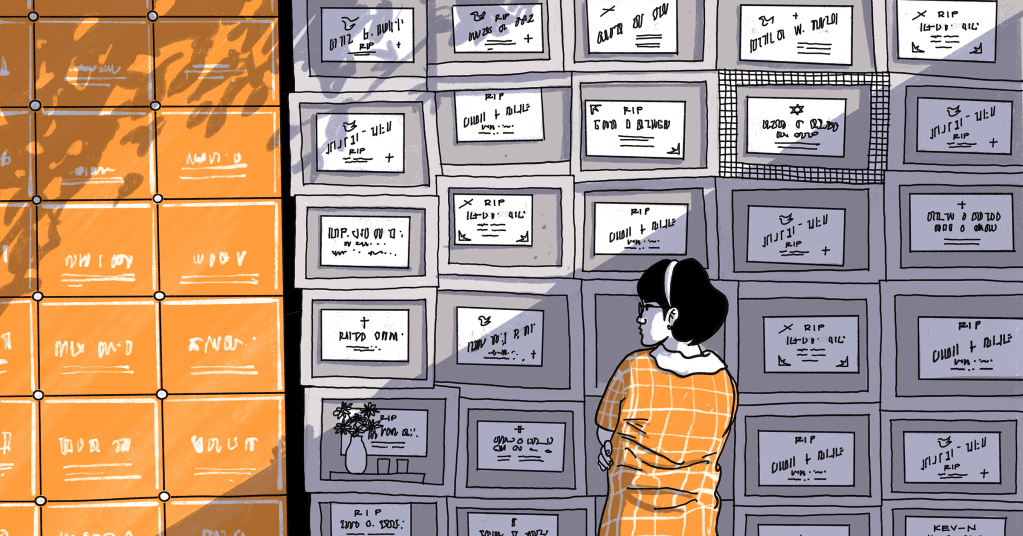

He walked home that afternoon and decided to pass through the cemetery. He’d already seen the construction photos in the meeting, but he needed the ten thousand steps so he might as well visit the real thing. He walked the narrow two-way street that led to the cemetery and as he got nearer, a single noticeable color started to emerge from the distance. Orange squares, the hallowed boxes of the Makatizen dead, peeked proudly above the fence in different directions. They were blending beautifully with the violet dusk sky. The new look grew on him. It reminded him of the boxes of toys with big heads lining up a wall in his home.

After the sun melted into the horizon, Froilan headed for home. He walked the gauntlet of narrow sidewalks, crooked alleys and strings of cheap motels. In one of these establishments, he saw a couple holding hands, filled with post-coital glow, stepping out of the motel doors. A familiar scene.

“Ahh,” he said to himself. “It was not Eddie and Thea after all.”