Kai, my youngest son, nearly fell from a foot-high concrete cube. The pedestal he was playing on was one of the hundreds running the length of the roof deck. These tombstones were once the supporting bases for clotheslines that the homeowner association decommissioned in favor of the more modern laundry cages. By extending his arms, Kai was able to correct his balance just before reaching the tipping point.

Even though he can’t maintain eye contact, I can see in his quick glances that he was determined to step down on his own. By all means he can, but an invisible force seemed to block all his efforts. His doctor said that Kai has an inherent difficulty in motor planning. That’s the reason he never learned to point fingers before turning six months old, and why he still couldn’t speak a single word at eighteen months old.

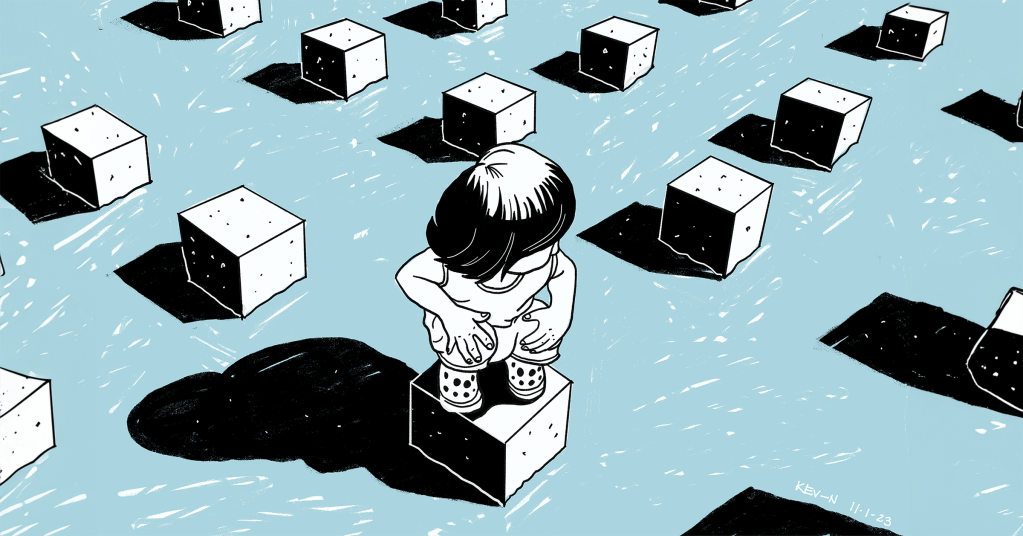

He tried to step down from the pedestal again, this time pointing his toes to reach the ground, as far as his balance and limbs would allow. He almost made it, but second-guessed himself at the very last second. The news that Kai was somewhere on the autism spectrum was still fresh, and seeing him play this way, all alone in his world, was confirming the headline. I wanted to help him, but there was also a side of me that wanted to risk his body just to prove the diagnosis wrong. The child’s play was suddenly a serious experiment, with scratches and scars as acceptable consequences.

I went to him, held his hand, and helped him down.

My youth is vastly different from both of my sons’. My body is a map of my adventures and misadventures, with scars marking the spots. One such spot is a scar above my left elbow that looked like a poorly drawn caterpillar. I got this caterpillar while swimming along the gray sand beach of my childhood hometown. I jumped into the water, oblivious to the broken bottle that waited for me underneath. If not for the tickling sensations, I wouldn’t have known that small fishes were feasting on my open wound. I bolted to the nearest adult I could find, my lola’s first cousin, and got victim-shamed before being sent to my first ever trip to the hospital.

My shin has a similar story, albeit of a more self-inflicted nature. The scar is right on the spot of the shin that attracts step corners and table legs. This injury came from my usual summer itinerary that included exploration of my grandmother’s part of the woods, swimming in the river that bordered it, and snacking on some fruit trees that me and my company of young relatives meet along the way. Being the far flung village that it was, the casual walk into the woods necessitated us to bring a jungle bolo, if not to kill snakes or protection against aswangs, at least to help clear the weeds and overgrown bushes that covered the foot paths, or to simply chop a coconut for the buko juice.

Village kids are well acquainted with the benefits and dangers of the jungle bolo. As a poblacion kid, I was not. I played with it. I hit the trees with it. I swung it at the water while we walked down the stream. I did not intend to swing it towards me, but the unpredictable way a flat metal surface interacts with liquid water made the jungle bolo come at my leg with force.

The blade hit my shin where the flesh is thinnest between skin and bone. At first it was just a bloodless slash. No harm, no foul. Then the wound opened up like an eyelid, revealing the proverbial white priest, or skin fat, from within. It then weeped a continuous stream of crimson. On cue, Auntie Lenny who was weirdly just two years older than me, grabbed a nearby Hagonoy bush and chewed some of its leaves. After a few seconds she spit out a mushy ball of greens and shoved it to the now bloody gash on my shin. Someone from the group inexplicably found a black bikini brief floating along the river, ripped it in half and made a bandage out of it. To this day, I am still thankful for the careless labandera who donated the sexiest wound dressing known to man.

On the later part of my elementary days, we moved to a more urbanized part of the province. My mother, a policewoman, got detailed as the assistant to the PNP Provincial Director, the biggest of the big wigs. As a result I became a beneficiary of the trickle-down perks of the job. On one of the officer’s excursions to the beaches of southern Palawan, I got stung by a box jellyfish.

The damage from this incident left a hotdog-on-a-stick-shaped scar on my right leg, about eight inches long. Me and Hannah, the officer’s daughter, were playing on the shallow waters when I felt a sharp and itchy sensation down on the inner side of my right leg. It felt like being hit with a leather belt, only that the belt was made out of a million needles. I thought that maybe I stepped on a mangrove shoot or that a colony of angry sand mites were after me. I walked towards the shoreline to check my leg. As I sat, I saw Hannah pick up a floating white mass from the edge of the water, then throw it on the sand. It looked like a big soft nata de coco.

A crowd gathered around the thing, then oddly, gathered towards me. It was the moment I found out I got stung. A gelatinous thread-like piece of tendril was stuck to my leg, the same type of tendril that the jellyfish on the sand had. It oddly smelled of seaweed. A person from the group dumped a fistful of sand on my leg and used it as a scraper tool to unstick the tendrils from my skin. The cool sand was soothing but not enough to alleviate the pain of a thousand cuts I was experiencing. Then someone poured vinegar on my leg only to be told by the on-duty lifeguard to use warm water and soap instead. The portion touched by the vinegar became the hotdog part of the scar, the portion washed with soap and water became the stick part of the scar.

As we were heading down the stairs, the reality that Kai has autism struggled to sink in. I didn’t know how to feel. I didn’t know much about ASD at that moment. I didn’t know what to do. I carried him down the fire exit. We bumped heads. I kissed his forehead as an apology and noticed that the forcep marks on his head were gone. These temporary dents were the result of his complicated birth. With the umbilical cord wrapped around his neck, he needed to be forcibly pulled out of his mother’s womb.

I realized in that moment that my son too has his own map of scars. He survived a life-or-death ordeal even before having a name, a much younger adventurer than me. I looked at him intently for a few seconds, then continued our journey back to the house. As we stepped down the stairs, I told Kai, “You will be okay.”