(7-minute read) On May 27, 1906, two Coast Guard cutters arrived in the island paradise of Culion, Palawan. They carried 370 passengers, fetched from various locations in the Philippine Islands, some with visible lesions on their skins, some with deformities in their limbs and extremities. These passengers were determined to be suffering from Hansen’s disease, commonly known as leprosy. They were ordered to segregate to this island colony by the Taft Commision, the American colonial government at the time. A colony within a colony, Culion received passengers from these so-called ‘leper collection trips’ until its decline in the 1950’s.

More than a hundred years later, Filipinos find themselves in the same predicament. SARS-COV-2 has forced the country to establish modern ‘colonies’ for the infected. Cities and provinces are dotted with quarantine centers made up of hotels, motels, repurposed multi-purpose halls and basketball courts—an architecture of isolation made of plastics and fabric.

The Evil Twin

From leprosy and bubonic plague, to smallpox and cholera, every stage of human progress is rife with its version of a deadly disease. The discovery of agriculture and animal domestication led to the invention of houses, but it also led to animal-borne diseases. Palaces, temples, and tombs became symbols of power, allowing god-men to walk the earth. This gave reason to wage wars which in turn gave rise to fortifications of stone. Commerce birthed ports and roads, humanities created libraries and educational institutions. As populations grew and mobility between city-states moved faster, so did plagues and sickness.

Operating without theoretical knowledge of how diseases work, people of antiquity relied on isolation and limitation of movement as means to hinder the proliferation of epidemics. Leviticus written between 7th and 5th century BC has instructions for isolation with a specific number of days for people suspected with leprosy. In AD 542, The Plague of Justinian enforced laws, although discriminatory against minorities, that prohibited certain people from moving in and out of the capital of Byzantine. In 1423, Venice established the island Lazaretto Vecchio as a leprosarium where all the infected will be brought for isolation.

Now, with our sophisticated understanding of epidemics, quarantine and isolation has become standard practice in delaying the rate of infections. The World Health Organization has warned us that COVID-19 will not be the last pandemic. We Filipinos must then accept that much like cancellations of classes during typhoons, lockdowns and community quarantines will be a new part of our lives.

The Conundrum of Flexible Spaces

Much has been said about open planning, both in the residential and commercial segment of designed spaces. Open plan is an attractive prospect especially in megacities with scarce floor areas. But with the arrival of COVID, many industry thinkers opined that the open plan concept has finally died. I would not be so sure.

Barriers and distance are the main ingredients of a pandemic-resilient design, but flexible spaces are the ones that enable it.

Flexible spaces can pave the road for the architectural solutions ahead. The concept is not new. Movable wall partitions, the Shoji, are an important element in Japanese architecture for more than a thousand years. Unlike the western idea of doors, these panels can fully open and close a space, or connect it to an adjacent space depending on the need at a particular time.

Another avenue that can be explored is the copcept of transient use. Designers should develop an aversion to fixed-in-place furniture and decorative elements.To paraphrase a quote I often hear, everything must fall when one turns a house upside down. To truly create places of comfort, productivity and security in an age of uncertainty, architects must design spaces that allow for multiple use—a bedroom today, an office tomorrow.

Welcome the Elements

A byproduct of being mostly indoors, people have started turning to plants as a source of experiencing nature. Plantitas and plantitos ordered in droves for plants, at first scouring choices for their health benefits, and later for their perceived rarity. The current crisis has reaffirmed our inate dependence to nature and also our general susceptibility to fad.

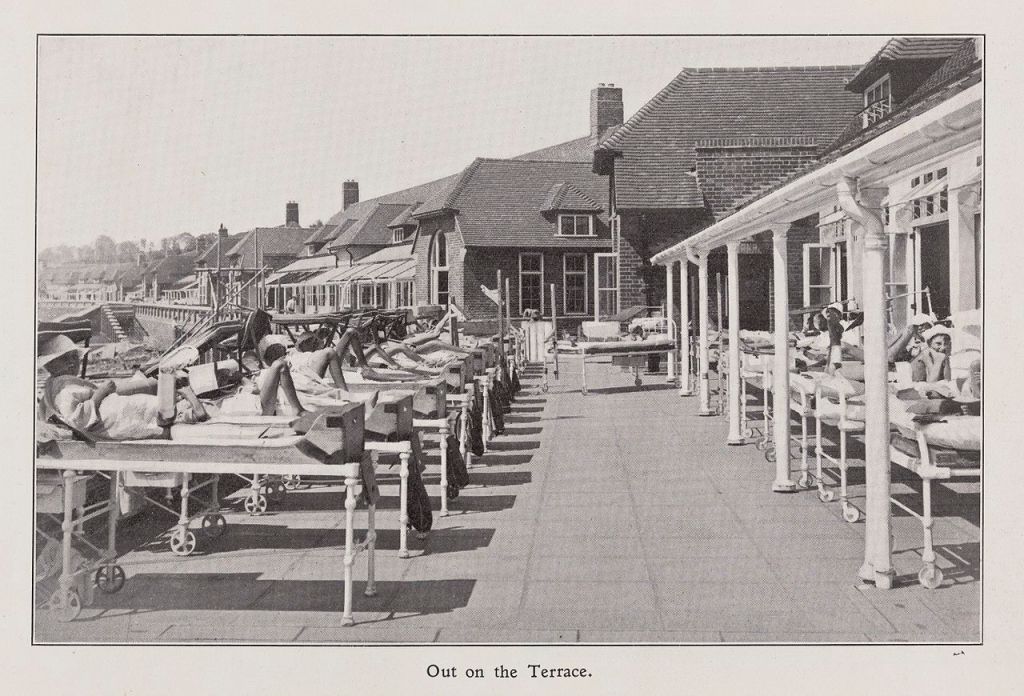

In order to design healthier spaces, architects must study the connection between and personal health and nature. Before today’s treatments, sanatoriums of the past prescribed heliotherapy as treatment to tuberculosis patients. Beds are lined up in a space called ‘sleeping porches’, with large open windows oriented towards the solar path. Patients lie down and spend a certain time of the day bathing in the sun. The practice is eventually stopped with the discovery of antibiotics, but physicians are baffled by the seeming efficacy of the therapy. New scientific findings today are slowly confirming the effect of Vitamin D in the treatment of tuberculosis in tandem with medications, but in the past people have intuitively sought remedies in nature.

For a country like the Philippines, with a 75% average annual humidity and a 34 °C average high temperature, exposure to nature might be a pill too bitter to swallow. But there are alternative means. This includes reasserting the principles of building orientation to light and air in the design process. Maybe it’s time to rethink the conventions of facade design and prioritize the size and positions of building openings, length and height of eaves with regards to sun angles and prevailing winds.

A bigger step still is the recognition of landscape architecture as an integral part of residential design. The customary belief that landscaping is reserved to the ‘tira-tira’ space, the area left after the building setback requirements, must be set aside. When done right, landscape design provides cures for the common ails of the tropical space—shade from the sun, shield from tropical typhoons, natural ventilation, and an improvement in indoor air quality. In its essence, architecture for the post-COVID world is environmental design—access to clean air, ample light, and safe water.

Equitable Spaces

The Bubonic Plague with a death toll of 25 million in the 1500’s alone forced city-state planners to design for larger and less cluttered public spaces. In 1854, John Snow, the father of epidemiology, found a link between cholera outbreaks and contaminated drinking water, paving the way for nations to invest in clean water supply and proper sewage infrastructures. Typhoid, polio, and Spanish Flu compelled cities to clear slums, provide tenement reform, waste management and a clear separation of residential and industrial districts. The world is littered with architectural reactions (and ancient ruins) to historical epidemics. Valuable lessons can be extracted from them. But lessons are only valuable if they lead to actions.

One of our neighbors, Singapore, is a success story in building design standards and compliance. All relevant laws, guidelines, and subsequent requirements are available online and updated regularly. Submissions are also digital, complying to global standards of Building Information Modeling. This enables accuracy and quick checking of compliance to existing building laws, not to mention the speed of transactions—a far cry from what is currently happening in the Philippines. Singapore has shown that urban renewal is an outcome of political strength and robust government agencies.

Our professional organizations must set aside political obsessions and feudalism. Allied professions must unite and lobby for an updated and unified building code. The 44 year-old National Building Code must be revised and adhere to the most stringent and advanced building safety requirements of the century, including the considerations for health, wellness, and environmental sustainability.

The passing of The Philippine Green Building Code as a referral code is a step into the right direction, but local government units must also adhere to their respective Comprehensive Land Use Plan (CLUP) regardless of change in leadership every three years. Real change comes from the adoption of the generaal populace and the ability of the leadership to enforce it.

An architecture of the future is a tempting solution to the troubles of the present. But like the flu, the spatial problems revealed by the pandemic are just symptoms of decades-long negligence to a simple fact. Spaces for humans are spaces for life.

Until we learn to create houses and cities in accordance with this fundamental truth, we are much like the passengers of the two Coast Guard cutters that arrived on a tropical island on May of 1906—isolated and waiting for the inevitable.

This blog post is the abridged version of my article for Bluprint E-mag Vol. 1 2021. You can read the full version here or Bluprint’s own short version here.